The Aim of Christ’s Cross

by Bob & Kent

There are a few ideas connected with Christianity that have haunted some of us over the years. These thoughts aren’t exactly conscious thoughts, out in the foreground in plain sight. They lurk back in the shadows, providing only an occasional, fleeting glimpse of themselves. These apparitions are not friends of reason. They flee in terror from thoughtful analysis.

One of the phantoms is the concept that Christ’s death on the cross was a payment for our sins so that God could forgive us, even though this kind of thinking stands in sharp contrast to the plain words of Jesus.1 Jesus maintained that he and the Father are one and it is not necessary for him to pray the Father for us, “for the Father himself loves you.”2 Many well meaning Christians hang on to the notion that Jesus’ payment for our sins was made to make amends with the Father, to somehow get Him to accept us. Although the words placation and appeasement are often dodged in personal discussions of the atonement, the message of an offended deity needing to be pacified subtly gets through.

We sing the lyrics, "Jesus paid it all…" and, "He paid a debt he did not owe. I owed a debt I could not pay…" Certainly this payment imagery conveys the desperateness of our plight and speaks to the necessity of God’s involvement in rescuing us from that situation. Relief from our debt is said to come in the form of a free gift from God. Free applies to us, not to God. For Him there was a cost. Cost is another word lending itself to the payment theme.

There is an inherent awkwardness in this scenario, though. By reducing this free gift of God to an entity or commodity that can be bartered, or bought, or bargained with, there arises the strong suggestion that this most unique currency, Christ’s death, was paid to someone. The question thus emerges, to whom was this payment made? Who would extract such an awful price for the redemption of sinners?

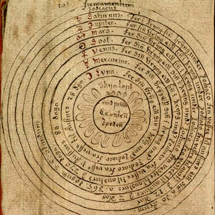

Over the years, Christianity has struggled with this question. How does one interpret debt payment and to whom the payment was made? Answers range from The Devil all the way to God The Father, with various explanations in between.3 The attempt is made to treat the meaning of Christ’s death as a mystery, not to be understood till the hereafter4 as well as to shift the focus onto the reality of the payment, attaching little significance to whom the recipient was.5 In the context of humanity establishing a saving relationship with God right now, discovering who gets paid off is of major import. For if it is God that receives payment, then this speaks directly about the nature of the recipient.

The Bible, while allowing this comparison with payment to illuminate the crucial importance of Christ’s act on the cross, does not inform the reader to whom this payment is made.

If the Devil was being paid off by Christ’s death, then we’re left asking why God was indebted to him. Was God paying off the Devil so that he’d leave us alone? Why would the Devil be true to his word in such a deal? Contrary to some viewpoints, humanity has never been the property of the Devil to start with. The Bible does teach that we are slaves to sin6, but nowhere does it literally teach that we are slaves in the ownership of the Devil. Moreover, how would the Devil have gained ownership of us to begin with? Most Christians rightly reject the notion that payment was made to the Devil.

If God was being paid off by Christ’s death, we have a bigger problem than with the scenario mentioned above. It would be a troubling stretch of logic indeed if God (the Son) made payment to God (the Father). Furthermore, what kind of being would require this cruel action in order to be satisfied? Is this the kind of being you would like to be around throughout eternity? Surely the answer to this question makes a powerful statement about how God operates His universe and goes to the very heart of the character of God.

Instinctively one recoils from the specter of a God demanding His Son’s blood as payment. Relief from this dilemma is sought in the suggestion that Jesus was not appeasing God the Father by his death, rather, He was satisfying the Law. God’s Law had been broken and the penalty — death — had to be paid. Jesus died to satisfy the requirements of God’s Law.7

This sounds like a convincing objection until one realizes that behind every law that has ever been conceived, there stands a person or persons. Laws are inanimate ideas. They neither gain satisfaction nor lose it. Laws simply reflect the thinking of those who institute the laws. Personification of an idea mustn’t be taken literally. Only beings are satisfied.

To separate God from His Law in hopes of absolving Him of the horror that this payment imagery evokes is totally inadequate. To suggest there is something outside of God, or other than God, to which God is beholden — to which He must answer — is unfounded since Law itself originated from God.8 The Bible equates Law with Love.9 And Love is inseparable from God. Thus Law cannot receive payment or be satisfied apart from God being satisfied or receiving payment.

So where does this reasoning about the Law being satisfied lead? It leads right back to saying that The Father had to be satisfied by Christ’s death. It leads to a picture of God needing to have His wrath appeased in order to be as forgiving, as gracious a person as Jesus.

It should be noted that payment of debt is not directly spoken of in scripture. This concept is derived from the term ransom, which is used on two occasions by Christ10 and once by Paul.11 Evoking memories of His redemption of the people of Israel from Egypt12, ransom connotes deliverance and release, not payment. Clearly, with God’s release of His people from bondage, there was no payment involved. God simply took back what was already His. He freed them in a unilateral action for which He needed no permission from anyone.

The word propitiation, which appears 3 times13 in some English translations of the New Testament, clearly means appeasement. The meaning of the 2 related Greek words from which comes propitiation is far less certain, forcing translators to render these texts in a variety of ways.14

One’s concept of sin actually plays an important part in their understanding of this payment question. If sin is seen as offending an angry God, payment is needed to appease that anger. If sin is seen as specific acts, which are deemed wrong because rules have been broken, payment is needed to compensate somehow. But if sin is seen as an attitude of rebellion against God, then what God offers is release from the hold of that rebellious attitude. When sin is understood as a condition of being ignorant of the truth about God, then what is needed is reconciliation and restoration on our part. Payment or ransom can be seen as an analogy, but the analogy must not be pressed too far.

Closely related to this idea and further evidence of the limits of the payment metaphor is the realization that payment, per se, still does not accomplish what God really wants. A change of heart cannot be bought.15 Often, the suggestion is that forgiveness is what was purchased by Christ’s payment on the cross, and that forgiveness then enables salvation. But forgiveness is not the goal. It is simply a tool in God’s hand to free us of the sense of shameful guilt that would hinder our coming to him for healing.

But perhaps the most troubling aspect of payment theology is that in essence, it is idolatry. The hallmark of all false religion is the express need to act in such a way as to affect God’s attitude towards us. To infer that God or His Law requires payment implies that God can be convinced to change His stance toward us once payment is made. This stands in diametric opposition to the God presented in the Bible. Christ Himself came to show us the Father, a task He stated He had successfully accomplished.16 And nowhere is a relationship with Christ seen to require payment in order to establish this friendship.

The Protestant reformers recognized that we as sinners cannot hope to influence God by our behavior so they substituted Christ’s behavior for ours. This dynamic, often called righteousness by faith, still portrays God as needing to be persuaded to accept us. Since our own work is ineffective, our salvation depends on Christ’s work to influence God. This explanation suffers from the same flaw that pagan religions do; it portrays God as needing satisfaction of Christ’s perfect life in order to accept the sinner. But this fuzzy thinking contradicts Christ’s own words. God needs no convincing, for He loves us Himself.17 Anyone thinking along these lines imagines a god that doesn’t exist.

What, then, of salvation and payment?

It is not the intent of this essay to denigrate what, to many, is a comforting and inspiring teaching. Furthermore, it would be very arrogant of us to discount the efforts of so many godly people over the centuries working with the best of intentions. For us to disagree with someone’s conclusions doesn’t necessarily cast disrespect. Paul urged those in Philippi to think things through for themselves, humbly and carefully.18 This advice leads us to examine more closely the meaning of the Christ’s cross.

The seriousness of humanity’s condition, the depths of love that would move Christ to be willing to endure such selfless suffering and pay the price for our redemption are themes that cannot and should not be denied. It must be recognized however that payment imagery is but one of many metaphors used to illuminate the meaning of the cross. Other images employed by the Bible include the court of law, the world of commerce, a personal relationship, sacrificial worship and the battleground where good triumphs over evil.19 The difficulties described with this metaphor illustrate the inherent dangers taking a metaphor beyond its useful and intended purpose.

To call this imagery a metaphor in no way diminishes its meaning or indeed the importance of the cross. Indeed it must be recognized that there are many metaphors used in the gospel story to illuminate the meaning of the cross. The discomfort one feels when struggling to make sense of the payment model should motivate one to a deeper study of the infinite depths of meaning contained by the cross. This paper only hopes to dramatically demonstrate the limits of payment analogy when taken literally. One is spared the awkwardness of explaining why God would require such a dramatic sacrifice (when He Himself claims to love us) if it is understood that it is as if the cross were payment for our sins.

The Bible teaches that Christ’s death on the cross reconciled the whole universe to God and introduces the idea that even unfallen angels somehow needed the crucial evidence which the cross provided.20 Since angels have not sinned, debt payment would be unnecessary for them.

The Cross can be seen as the ultimate demonstration of the truthfulness of God’s word and the reality of His warning in the garden of Eden. When God cautioned that distrust and separation from Him would result in death, the universe, never having seen death, could be misled in assuming that God would in fact kill those who reject Him. This perception would result in God being worshiped from fear, a motivation that trivializes the kind of relationship that God desires to have with us.

God did not ask a created being to demonstrate the truthfulness of his word. He, Himself, died the death of the sinner. Christ faced the guilt-prompted separation from his Father as he experienced the mental anguish from our sin. This agony, which began in the garden, caused Him to cry out, “If it is possible, take this cup from me.” This selfless demonstration of the truthfulness of God’s loving warning regarding sin can be said to have cost the life of Christ. What Christ bought with His life was irrefutable evidence that God is truthful and worthy of our complete trust.

Who needed this proof? For whom was the evidence provided? Both the fallen sinner and the onlooking universe. Any rational being who might ever question the results of sin has received a most satisfying payment. In a very compelling sense, the payment of Christ’s death was both for us, and to us. For it is we who must be won back to trust, the condition of at-one-ment with God.

God conceived of this plan for clarifying His own truthfulness, not because of anything owed to humanity. The plan preceded the creation of humanity.21 Rather, it was to reveal the infinite love of God to the universe, a love that would go to such lengths in preserving the freedom of choice endowed to His creation. There’s nothing haunting about discovering this truth about God. This truth isn’t a ghostly idea that dissolves into nothingness with illumination.

The great news about God is that He did not require or need blood payment in order to accept us. He was willing to pay with the very life of His Son the cost of winning us back to trust. This is the aim of Christ’s cross.

1 John 14:9,10

2 John 16:25-27

3 Joel B. Green & Mark D. Baker, Recovering the Scandal of the Cross (Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press, 2000), p. 21-23.

4 Hans LaRondelle, Christ Our Salvation (Mountain View, California: Pacific Press Publishing Association, 1980), p. 22

5 George Reid, "Why Did Jesus Die?" Adventist Review, (November 5, 1992), p. 11

6 Romans 6:6, 16-22

7 Matthew 5:17

8 Colossians 1:16,17

9 Matthew 22:36-40, Romans 13:8-10, Galatians 5:14, James 2:8

10 Matthew 20:28, Mark 10:45

11 1 Timothy 2:6

12 Exodus 6:6, 16:13

13 Romans 3:25-36; 1 John 2:2, 4:10

14 Romans 3: "by his sacrificial death he should become the means by which people’s sins are forgiven" TEV; "expiating sin by his sacrificial death" NEB; "a Mercy-seat, rendered efficacious" Weymouth 3rd Edition; "sacrifice of atonement" NIV; "a sacrifice of atonement by his blood" NRSV; "an expiation by his blood" RSV | 1 John 2: "expiation for our sins" RSV; "atoning sacrifice for our sins" NIV/NRSV; "remedy for the defilement of our sins" NEB; "the means by which our sins are forgiven" TEV

15 see Ps. 51

16 John 17

17 see John 16:26

18 Philippians 2:12

19 Joel B. Green & Mark D. Baker, Recovering the Scandal of the Cross (Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press, 2000), p. 23.

20 Colossians 1:20

21 Ephesians 1:4, 1 Peter 1:20